FPPS Is Not a Free Lunch for Bitcoin Miners

Bitcoin mining is a complex business. When someone plans to use economic resources to mine traditional commodities such as gold, copper, or oil, prior exploration of these resources is always done to ensure that the investment in a mining project will not be in vain. However, due to the very nature of Bitcoin’s security protocol, miners cannot do exploration because finding a block is a random and statistical process. Since only 144 blocks can be found per day, there is no way to guarantee that a miner’s work will be rewarded in a timely manner without significant volatility unless they have a significant hashrate. To consistently pay out and significantly reduce the variance of revenue, a miner needs approximately 1.2% of the total hashrate (about 10 exahashes per second at the time of writing). The capital expenditure to achieve this level of hashrate is in the hundreds of millions of dollars. Unless the miner is a large organization with a large number of ASIC machines, it will be difficult.

To solve this problem, mining pools were created. Consider a single miner with a small but significant stake. Out of 52,560 annual blocks, he must find one, as his stake is 1/52,560 of the total network hashrate. In simple terms, he must find one block every 12 months. However, his electricity bills come every 4 weeks, and if he waited a whole year to pay the bills before receiving income, he would go bankrupt. Given this discrepancy between current expenses and income, he comes up with an idea. He decides to team up with 499 other people with similar mining volumes, and they enter into an agreement. Instead of everyone mining individually, the miner proposes that they all work together as if they were part of a single organization, dividing the mining reward according to each miner’s contribution, every time someone finds a block. If each miner had 1/52560 of the total network hashrate, then 500 miners would collectively be expected to find a block about twice a week. With a pool approach, each miner ensures that all the effort and hard work they put in will be rewarded much more frequently. This way, everyone will be able to pay their bills every month, and by the end of the year, they will all avoid bankruptcy. However, there are still sources of variation in these payouts.

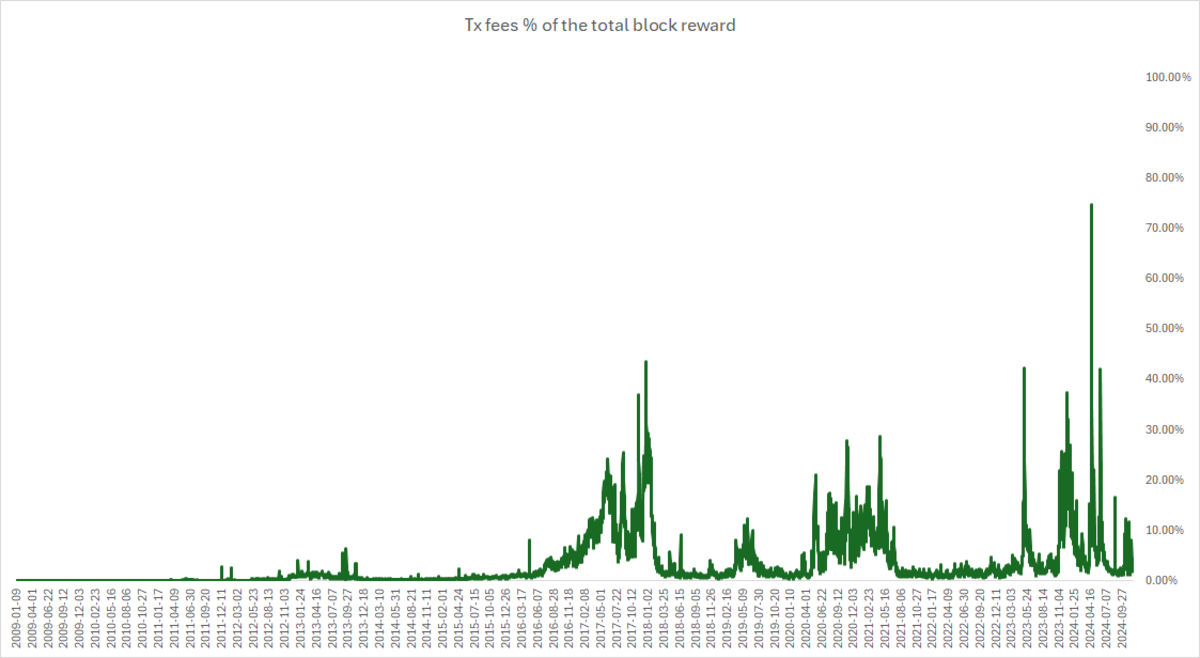

Pool mining ensures that miners will receive payouts much more frequently than if they were mining individually. However, it does not provide predictable payouts based on the hashrate each miner has. This problem is known as pool luck risk. Let’s go back to the previous example. 500 miners, each with 1/52560 of the total network hashrate, should end up finding 500 blocks per year. However, they could find 480, 497, or 520. There is no guarantee that the pool will mine exactly 500 blocks per year. Pool luck is calculated by dividing the actual number of blocks found by the expected number of blocks based on the pool’s total hashrate. If a pool finds 480 blocks when it expected 500, the pool’s luck would be 95%. Pool luck can cause significant fluctuations in revenue over short periods of time. However, luck usually evens out over time, and the payouts will eventually match the expected distribution based on the pool’s hashrate. Two additional factors affect the overall variance of miner rewards, with the first factor having a more significant impact than the second. The first factor is transaction fees. These tend to fluctuate significantly, as has been seen in recent years. Transaction fees from blocks mined immediately after the last halving accounted for more than 50% of the total block reward for the first time in Bitcoin history. At the time of writing (block height 883208), there have been several partial blocks mined in the last week, as the mempool has been cleared several times over the past few days. That’s quite a significant jump in a short period of time. The second factor has to do with the variance caused by the time between blocks found by the network. When a block is immediately after another, transactions have less time to accumulate in the mempool, resulting in lower transaction fees in that block. Conversely, if there is a longer period between blocks, more transactions will be broadcast, resulting in higher transaction fees.

During the 2024 halving, for the first time in Bitcoin history, daily transaction fees paid to miners exceeded the block subsidy.

During the 2024 halving, for the first time in Bitcoin history, daily transaction fees paid to miners exceeded the block subsidy.

Uncertainty is painful. Especially when there is significant capital risk. That’s why most miners value more predictable, stable, and less volatile payouts to compensate for the significant capital invested. This is where the all-fee-per-share payout scheme offered by pools comes in. FPPS functions like a traditional insurance product. It is a pure risk transfer. No matter how many blocks a pool’s miners collectively find or what the transaction fees paid for them are, miners are paid by the pool based on the expected value of their computing power. The pool bears all of this risk. The predictability that FPPS provides miners is unmatched by other methods. It’s no surprise, then, that FPPS has now become almost the standard for pool payouts, albeit not without significant costs.

FPPS is not a free lunch. Pools need large amounts of capital to withstand any down periods and risks associated with the FPPS payout scheme. These high capital requirements come at a cost.

Source: cryptonews.net